Note: This was originally published in Pacific Fishing. The photographs come from NPS and from the University of Washington's Freshwater and Marine Image Bank.

The chef slid the lid off a small, wooden box and pulled out a plastic bag of stiff, milky-white cod. After soaking the fish, she boiled potatoes with fresh herbs and white wine. The mashed potatoes were pressed with the mashed cod into cakes, pan fried and served with a poached egg and hollandaise sauce. After that meal, salt cod benedict vies with shrimp and grits as one of my favorite breakfasts, ever.

To the disappointment of some gastronomes, the heyday of salted fish has long passed. Before the proliferation of refrigeration, salting was an expedient way to preserve fish while still on the fishing grounds. Moreover, most households didn’t have refrigerators or freezers either, so salting products was a safe way to store protein at home prior to consuming it. Popular salt cod dishes included bacalao, lutefisk, and serving the product with potatoes and a white sauce.

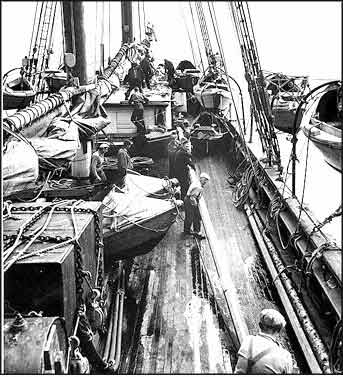

The earliest commercial fishery in Alaska was the salt cod industry. Shipwright extraordinaire Captain Matthew Turner of San Francisco is attributed with beginning the fishery within the Bering Sea in the 1860s. Later, Seattle, Poulsbo and Anacortes became the leading ports of Alaska salt cod landings because the retrofitted lumber transport schooners used in the fishery were ported in Washington State. Vessels like the Sophie Christenson, Wawona, John A. and others packed dories on deck and signed up a crew predominantly composed on Scandinavians. Dories were oar-powered until the 1920s, when 2 to 12 horsepower outboards were affixed to them.

Some hearty fishermen established shore stations in the Shumagin Islands and at Sanak Island. These on-shore processing facilities included warehouses for curing cod. There were 17 cod stations within the eastern Gulf of Alaska region by 1915. Fishermen lived in company bunkhouses and would row to the fishing grounds, twice a day. Ed Opheim, Sr. recalled that cod were so abundant around Unga that a red rag was all that was needed for bait. These shore-based fishermen also worked processing the catch at the end of the day.

As for those who operated from sailing vessels, cod fishermen brought their catch back to the ship for “splitters” to clean, head and gut. Experts could process as many as 6000 fish a day. Cod tongues were quite prized (creamed cod tongue was a particular favorite preparation); one person’s job was specifically to remove the tongues. After, the fish were thrown into a tank and retrieved by a “salter,” who laid the fish out and spread one pound of salt for every four pounds of fish. These stacks of fish were called kenches. The salt combined with the cod juices to create a brine, which cured the fish after two weeks.

The resulting product was often referred to as stock fish. Opheim describes how stock fish was converted into lutefisk, or so-called “Norwegian turkey, since it was eaten during the Christmas season. To prepare the fish for eating, one had to cut it into small portions and it was then soaked in a washtub of water. A spoonful of lye was added, which would make the cod soft, like jelly.” A hankering for lutefisk helped keep the salt cod industry afloat after refrigeration became common place. For example, the Pacific Coast Codfish Co of Poulsbo sold 100 tons of lutefisk each year. The company routinely delivered 600 to 1000 tons of salt cod each year.

By the 1930s cod had disappeared from the near-shore fishing grounds around the Shumagin Islands, necessitating the closure of many of the shore stations. Offshore vessels dominated the fishery henceforth. Sailing for cod persisted until 1950, when the C.A. Thayer made its last trip north. The captain, Ed Shields, claims that this fishing trip was also the last commercial fishing trip executed by an American sailing vessel on the Pacific Coast (though he must be excluding the double-ender salmon fishery in Bristol Bay).

The C.A. Thayer, photo from NPS.

Today, the C.A. Thayer is moored at the National Park Service’s San Francisco National Maritime Historical Park. In Alaska, remains of cod shore stations peek out of the sand. The cod fishery, of course, continues strong: in 2014, it accounted for 12% of the total harvest volume in Alaska. The market for salt cod in Brazil and Europe is substantial, yet according to the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute, “Alaska produces very little salted cod product.” That salt cod that I pine for on Sunday mornings comes from a processor based in Nova Scotia. Apparently, Alaska’s relationship to this tasty specialty product remains rooted in the past.

For more information on the history of the Pacific cod fishery, see Salt of the Sea: The Pacific Coast Cod Fishery and the Last Days of Sail by Captain Ed Shields. Or, wait until next year for the publication of James Mackovjak’s newest work, Alaska Codfish Chronicle: A History of the Pacific Cod Industry in Alaska.