Adapted from an article published in Pacific Fishing.

Beth Fields wiped the dirt from a peculiar button she found at her family’s set net site, exposing a gleaming, albeit worn, eagle crest. She discovered that the button likely once graced a Spanish-American War uniform. But, how would such a memento from the 1898 war make it to the Old Uyak set net site on Kodiak Island? And what does that war have at all to do with the seafood industry? It ends up, quite a bit. The button very likely was carried to Alaska in the sea bag of an early Filipino cannery worker.

It is indisputable that Filipinos have been the backbone of the Alaska cannery labor force. This is partly attributed to the Spanish-American War. Prior to the war, the Spanish crown controlled the Philippines. The Philippines became a U.S. possession soon after Commodore George Dewey obliterated the Spanish forces in Manila. The United States co-opted the Filipino’s long-lasting battle for independence from Spain. Instead of belonging to the Spanish, the Philippines now belonged to Uncle Sam. After the Spanish-American War, the US’s territorial holdings stretched from the isles of the Philippines to the salmon rivers of Alaska.

The timing of the war was fortuitous for American-owned Pacific enterprises that needed a source of cheap labor, especially Hawaiian sugar planters and Alaska salmon canners. Now that the Philippines was a US possession, Filipinos were considered American nationals. They were not citizens; they could not own property or vote. But as nationals, they could travel to the US without a passport and work.

Once the new Filipino immigrants arrived in the US, many hopped on a boat in San Francisco or Seattle and headed north. They were on their way to remote salmon canneries, like those in Uyak Bay. Included as passenger might have been the man who presumably carried the American-issued military jacket on which the eagle-crested button was affixed.

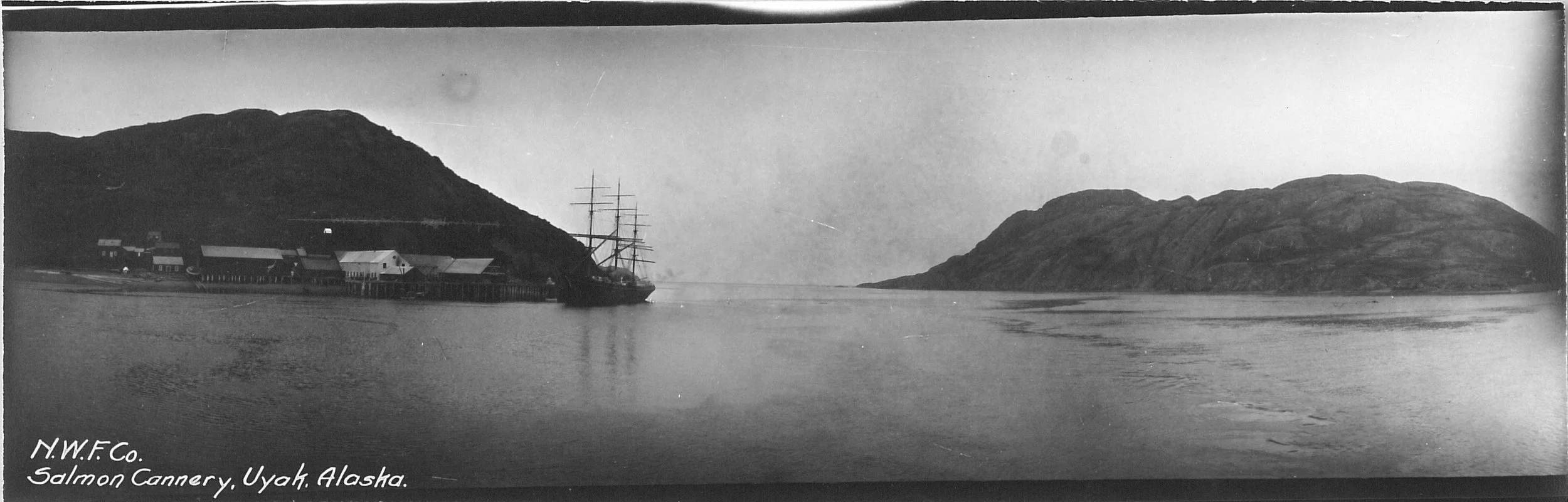

One of the two canneries built at the Uyak Achorage, just inside Uyak Bay on the west side of Kodiak Island. Image from the collection of Anjuli Grantham.

It was just one year before the war (1897) that two canneries were built near the Uyak Anchorage, where the Fields family’s set net site is today. Cannery worker demographics extracted from old federal salmon reports indicate that at the turn of the twentieth century, most of the Alaska cannery crew hailed from Japan or China. Yet, Alaska’s salmon packers were in need of a new, cheap labor supply to replace the aging Chinese workers. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 severely limited the number of Chinese who could enter the US. Thus, new recruits were needed to solder cans, butcher fish, and the myriad other tasks required to put up cases of salmon. Filipinos, these new American nationals, fit the bill. What started as a trickle of Filipino workers to Alaska canneries turned into a wave, so much so that by the 1930s, Filipinos outnumbered other ethnic groups in Alaska’s canneries.

We will never know who it was that brought that old Spanish-American War button to the cannery at Uyak. However, that one button reminds us that Alaska’s salmon industry has long been connected to global events.