Few images are more evocative of the history of Alaska’s commercial fishing industry than the sleek and sturdy profile of a Bristol Bay double-ender under sail. Thousands of these cannery-owned crafts were constructed in San Francisco and the Pacific Northwest and then sent north. Once in Alaska, a two-person crew composed of a skipper and “puller” was responsible for harvesting fish without the assistance of hydraulics while sailing, rowing, sleeping and living in an open watercraft in Bristol Bay. There is a reason why fisheries historian Bob King calls these fishermen the “Iron Men of Bristol Bay.”

Very few of these fishermen are still living, and few of the once-ubiquitous double-enders is still in sailing condition. One seaworthy double-ender is currently in Homer. The vessel is a so-called Libby boat, constructed and fished by Libby, McNeil, & Libby. The company had extensive operations throughout Alaska; in Bristol Bay alone it operated canneries at Koggiung, Ekuk, Nushagak, Peterson Point, and Kvichak Bay. The Libby canneries painted their double-enders butterscotch yellow to demarcate their boats from those of other canneries, a color that old-timers remember as “Libby orange.”

The federal Fish and Wildlife Service was responsible for managing Alaska’s salmon fisheries prior to 1959, when Alaska achieved statehood. Under pressure from the cannery lobby, the Fish and Wildlife Service contended that utilizing sail was a means to conserve Bristol Bay salmon. However, fishermen and many Alaskans knew what was really happening: canneries were reluctant to spend the money required to retool their fleets to accommodate power.

Only in 1951 did fisheries managers allow engines within fishing boats in Bristol Bay. As a result, the Bristol Bay salmon fishery is considered the last major commercial fishery to be wind-powered. Within a few years, the bulk of the fleet had converted to power, including the Libby boat which is now in Homer.

Dave Seaman owns the old Libby boat. Seaman is a shipwright and a member of the Kachemak Bay Wooden Boat Society. Seaman is hoping to sail the Libby boat back to Bristol Bay this summer and has teamed up with Tim Troll of the Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust and others to make this historic trip.

Photo courtesy Tim Troll

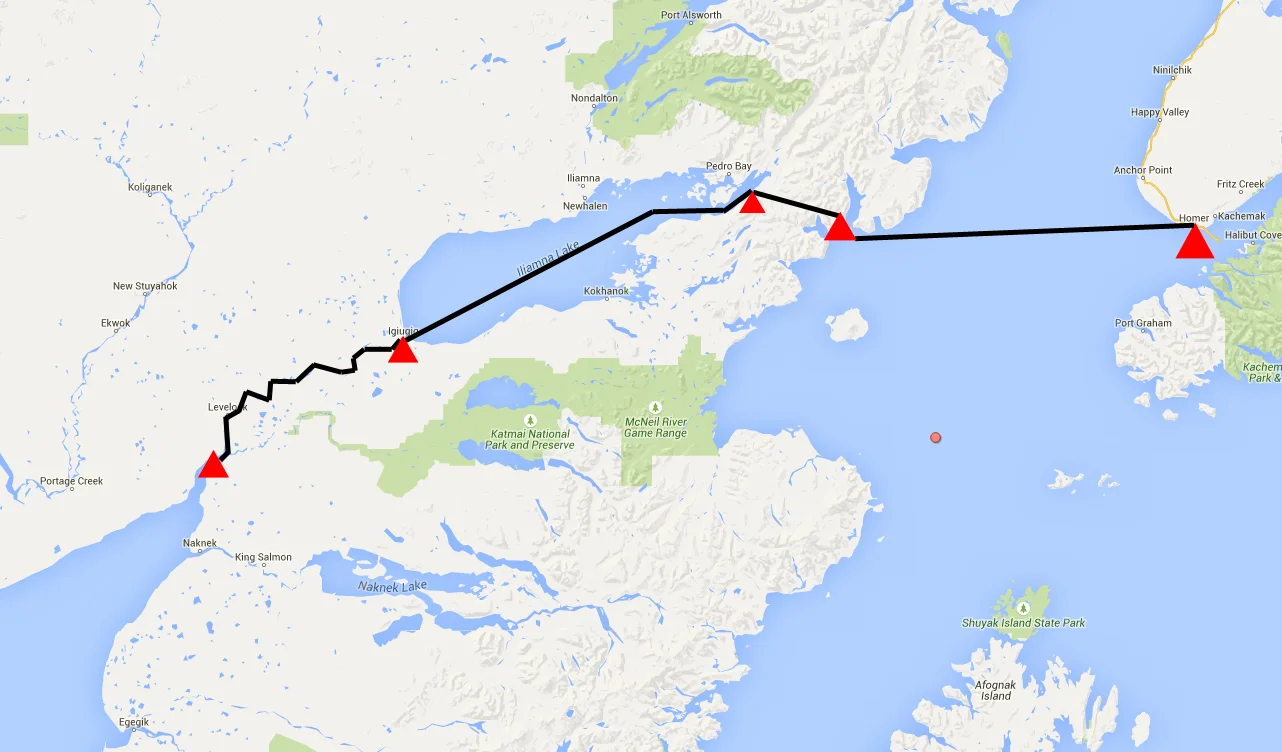

The Libby boat will take a route that hundreds of Bristol Bay boats follow each year, the Iliamna Portage. It will sail from Homer to the Alaska Peninsula, where it will portage through the Chigmit Mountains before rejoining water at Lake Iliamna. From there, it will sail across Iliamna and down the Kvichak River. “The tentative plan is to launch from Homer on July 4 and arrive in Naknek by the end of the sockeye season,” says Troll, right in time for the annual Fishtival celebration.

This journey will commemorate several important events in Bristol Bay and Alaska overall. For one, 2017 marks the tipping point in the Bristol Bay salmon fishery, in which there has been “66 years of sail and 66 years of power,” Troll explains.

Moreover, the sailing of the double-ender across Lake Iliamna will also highlight a significant step forward for sockeye salmon conservation in the region. The Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust is partnering with Pedro Bay Corporation and Iliamna Natives LTD to create the Iliamna Islands Conservation Easement, which will consist of 173 islands and 12,300 acres of prime sockeye spawning habitat within Lake Iliamna. “Lake Iliamna is the largest sockeye producing lake in the world and is the beating heart of the Bristol Bay commercial fishery,” explains Troll. “We will sail the boat through these [newly protected] islands.”

The return to Bristol Bay. Image courtesy Tim Troll.

Finally, it is 150 years since the United States purchased Alaska from Russia. Governor Bill Walker declared 2017 the Alaska Year of History and Heritage. Walker encourages “all Alaskans to take the occasion of this 150thanniversary year to study, teach, reflect upon our past, and apply its lessons to a brighter, more inclusive future.” Returning the Libby boat to Bristol Bay is a way to commemorate the birth of the commercial salmon fishing industry in the Bay, just in time for this statewide celebration.

The project is contingent on donations to cover the cost of a new sail for the boat, some basic maintenance, and the portage. Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust is leading the fundraising effort. You can help this historic double-ender sail home to Bristol Bay by making a tax-deductible donation to the project at www.bristolbaylandtrust.org.

For readers in Puget Sound interested in the history of double-enders, visit the APA Cannery Museum at Semiamhoo in Blaine to see the double-enders on exhibit. Moreover, Sailing for Salmon is a photo exhibit highlighting historic images from Bristol Bay, currently hosted at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences. Lastly, the new Alaska State Museum in Juneau features a Libby boat from the Koggiung/ Graveyard cannery.

The Koggiung/ Graveyard double-ender on exhibit within the new Father Andrew P. Kashevaroff State Library, Archive, and Museum in Juneau, curated by your's truly.