This article was initially published in Pacific Fishing.

Seventy five years ago, the United States entered World War II, leading to transformations that shaped the entire Pacific Coast but particularly impacted Alaska. Nearly six months after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the Japanese sent fighter planes to bomb the significantly less balmy Pacific islands of Kiska, Attu, and Unalaska. In early June of 1942, the village and military base at Dutch Harbor/ Unalaska were attacked and the islands of Kiska and Attu were invaded and wrested from American control. Attu villagers became Japanese prisoners of war and the Axis forces had a foothold on American soil.

The panicked military, Alaska territorial government, and Department of Interior determined to evacuate civilians who were 1/8 Native or more from the Aleutians. General Simon B. Buckner ordered the evacuation. Nine villages on the islands of Akutan, Atka, Umnak, St. George, St. Paul and Unalaska were hastily evacuated, precipitating one of the greatest injustices in modern Alaska history.

The military torched the homes and church at Atka and gave the residents one hour to leave. The USAT Delarof arrived at St. Paul on June 15 and departed the next day to St. George with the entire village on board. No more than one suitcase per person was allowed, and no one knew where the villagers were headed, not even the captain of the vessel.

The priest at St. Paul, Father Michael Lestenkof, recalled packing, stating, “For myself, I did not take anything except I took apart my five horse Johnson and put every part I can into one suitcase, except for the bracket and shaft, [which] was tied out on the outside of a suitcase, as I would make more use out of my motor than clothing.”

Villagers from the Pribilof Islands, on board the Delarof, en route to Southeast Alaska. Image courtesy NARA.

It was only when the boat was underway that a destination was determined. The evacuees would be kept at abandoned camps and canneries in Southeast Alaska. Quarters and provisions aboard the Delarof were poor. A baby girl was born on board and promptly contracted pneumonia. She was buried at sea near Kodiak Island, just the first of many who were to die from preventable illnesses over the next two years.

US Fish and Wildlife Service and other Department of the Interior employees were sent to assess the conditions of the derelict canneries and camps that were to soon house the 881 displaced villagers. The old herring plant at Killisnoo, an old mine and cannery at Funter Bay on Admiralty Island, an abandoned cannery at Burnett Inlet southwest of Wrangell, and Ward Lake Civilian Conservation Corps camp near Ketchikan were in varying states of decrepitude.

The canneries were constructed for just summer time use and had no insulation, indoor plumbing or heating stoves. At Funter Bay, just a single outhouse was built over the beach. In addition to lacking the basic infrastructure required for winter-time occupation, the sites had been abandoned years before and were either in need of serious repairs or actively rotting away.

The Delarof arrived at Funter Bay six days after leaving the Pribilofs. Five hundred and sixty people disembarked with little food, bedding, tools, or anything beyond that which they stuffed in one suitcase. The villagers arrived at the former complex of the Thlinket Packing Company. The cannery processed its first pack of salmon in 1902. It was sold to the Alaska Pacific Salmon Corporation in 1926 and then sold to P.E. Harris Co. It hadn’t operated since 1931. The government leased the abandoned cannery from P.E. Harris to be used for the “duration village,” as the relocation sites were termed.

The Pribilof residents got to work, fortifying structures, cleaning out the Chinese bunkhouse to turn it into the communal kitchen, and attempting to wire the buildings for electricity. But winter came quicker than building supplies, tools, and proper provisions, including ample blankets, soap, and more. The children were sent to the Wrangell Institute for school, which was difficult for the families, but at least meant that the kids had proper medical care and enough food.

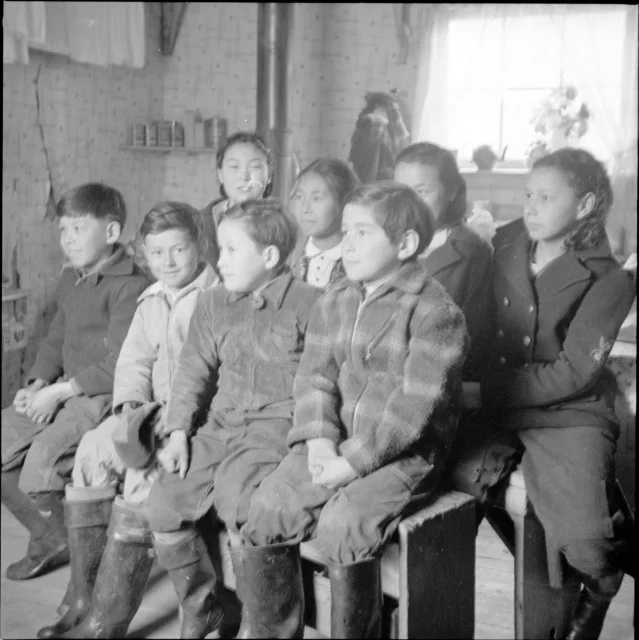

Aleut/ Unangan children at an unnamed Southeast Alaska cannery. Image courtesy NARA.

In the spring of 1943, US Fish and Wildlife officials informed those at Funter Bay that the men were to be sent back to the Pribilofs, but just for the annual fur seal harvest. During the forced relocation, the government continued to profit by selling the Unangan-harvested fur seal pelts to furriers. The Unangan hunters were falsely told the fur was needed for military uniforms, in order to coerce them to return.

Only in 1945, two years after American forces had retaken Attu and Kiska, were the Aleutian villagers permitted to return home. Yet at the Funter Bay cannery alone, 32 had died, mostly from pneumonia and tuberculosis. In total, seventy four people died while in Southeast Alaska, nearly one in ten of those who were evacuated.

Returning home was bittersweet. The village of Atka had been totally destroyed by the military, and the homes and churches within the other villages had been vandalized or worse by US military troops. The villages of Biorka, Kashega, and Makushin were never resettled. President Roosevelt authorized no more than $12 per person to assist in resettlement.

The Aleut Restitution Act of 1988 acknowledged that only an Act of Congress could help remedy these injustices. A community trust was established to assist in cultural preservation, education, and for elder services. Those evacuees who were still living received $12,000 each. Today few buildings remain at the old canneries and camps that housed the Unangan villagers, but the Aleut cemetery at Funter Bay continues to be maintained.