The first message was inside a plastic water bottle, the label worn and faded. The letter inside traced the bottle's origin to a cruise ship passenger, who, like the bottle, passed time ambulating around the Inside Passage. Julie Yates-Fulton was out on a beach combing excursion with her family when she found it, boating around the inlets and isles of Prince of Wales Island.

For the last several years, beach combing for Julie and a group of POW residents had turned into marine debris removal. This message in a plastic bottle befuddled the slippery classification system between sea treasure and sea trash. Plastic: trash. Message: treasure.

Julie's house and that of her friends in Craig are full of marine treasures. Glass balls from Japan, antique bottles, keys, marbles, molded feet from cast iron bath tubs--- these mementos from beach walks sit on the windowsills of many coastal homes. Switch the manufacture of these very objects from glass or metal to plastic, and from antique craftsmanship to recent production, however, and beach combing treasures become marine debris.

Beach treasures are precious and rare artifacts, they beacon the imagination. Marine debris is mundane, without individual merit. But even the most coveted of beach finds- the glass float- demonstrates that the divide is malleable. Japanese and Russian glassblowers made them on deck and attached them to trawl nets in the Bering Sea. These very factory trawlers fished right outside of the three mile limit delineating international waters before the 1976 Magnuson-Stevens Act, angering Alaskans. Glass floats= foreign draggers.

The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and the resulting onslaught of debris from the disaster continues to befuddle the distinction between trash and treasure. Trash: Japanese oyster floats, pieces of dock, packaging, household goods. Treasure: crates with expressive kanji characters, toys, castaway fish, and the basketball from the Kesen-Chu Middle School in Japan that washed up on a Prince of Wales Island beach. Julie is a teacher, and she started a pen-pal program with Kesen-Chu. Craig students exchanged letters and gifts with these other Pacific shore dwelling youngsters, connected by ocean and a single piece of marine treasure/trash.

Marine debris gathered from Prince of Wales Island beaches is available for viewing through the windows of the old Columbia Wards cannery office building in Craig.

Julie was pleased with her message in a plastic bottle that day, but she was supremely happy to be motoring on to her favorite cove of all. As the family cruised along, they passed canoe runs on the rocky shores, where stones had been cleared to the side to create safe passage for Haida and Tlingit canoes to launch and to return to shore. She and her family passed the remnants of traditional fish traps, some of which her own ancestors may have tended. These are special waters to the family.

They arrived at the cove and jumped ashore, toeing rocks and eyeing where beach and forest meet. Julie felt acutely present to that very moment. Her husband, Chad, said it was time to go and walked back to the boat; the others fell in line behind him. Chad started the motor but Julie persisted on shore. She was called to a certain corner, and although the boat started to pull away, she ran to the spot that beckoned her.

There, at her feet, was a glass float. Next to that was a green glass bottle stopped with a cork. A message was furled inside. In one day, Julie found two messages in a bottle.

She ran to the boat and hopped on board, clutching the glass float and the glass bottle in her hands. She paused, marveling at her intuition. Later, an elder relative told her, "You slowed your spirit down enough so you were in the moment and feeling everything."

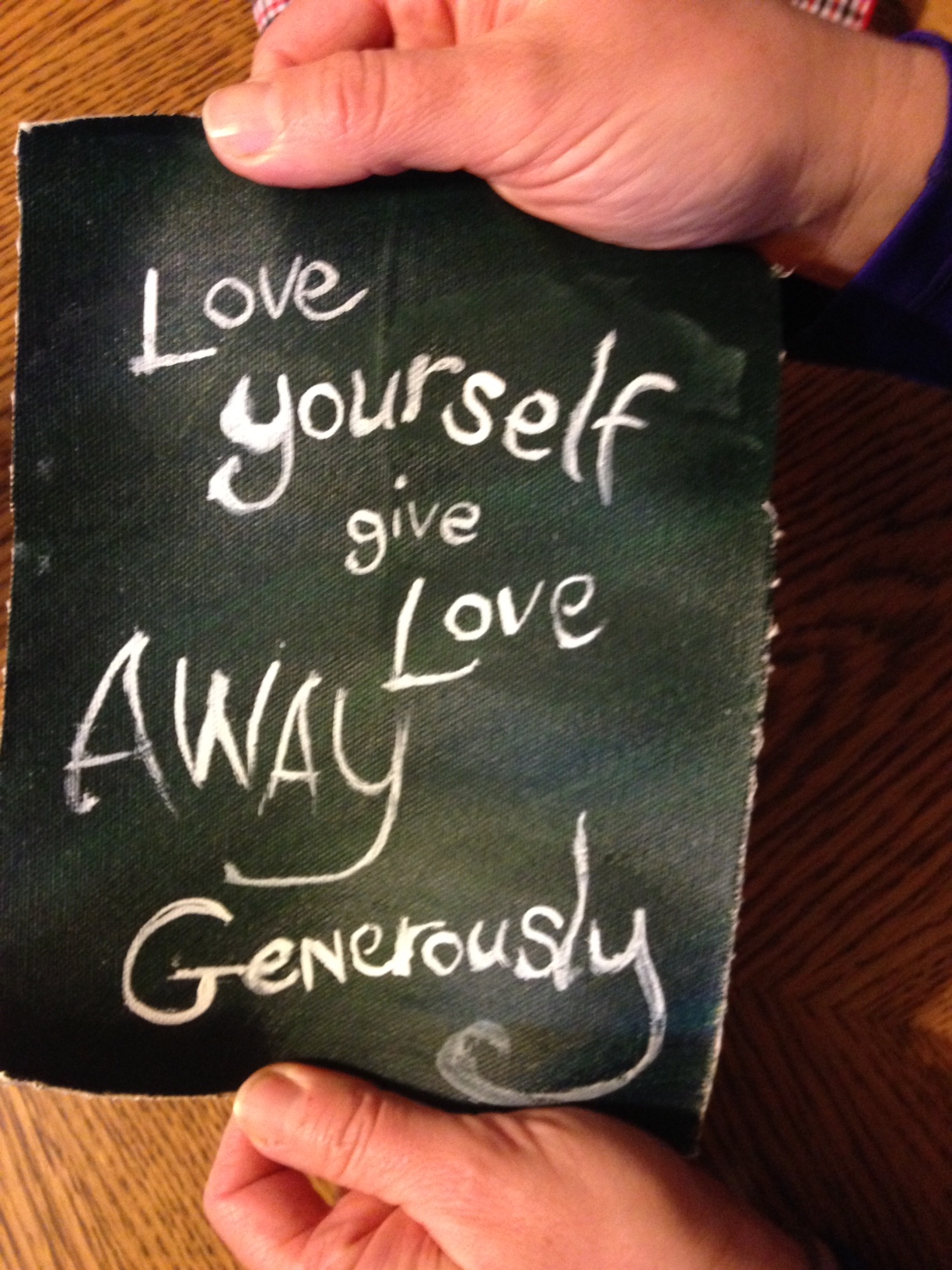

Julie uncorked the bottle and inside was this:

Truly, marine treasure.