The fabulous Kyla Villaroya edited this film for the ArtPlace proposal.

I don't like speaking highly of my gifts because it's embarrassing to do so. But, one of my greatest gifts is actually twofold. It is 1) receiving brilliant ideas from the universe and 2) finding the resources and building the network to make the ideas reality. So, this is what I've done since the spark hit me back in January. I found a potential funder (ArtPlace America's Creative Placemaking Fund), talked to the mayor and key collaborators, and articulated a vision for the project.

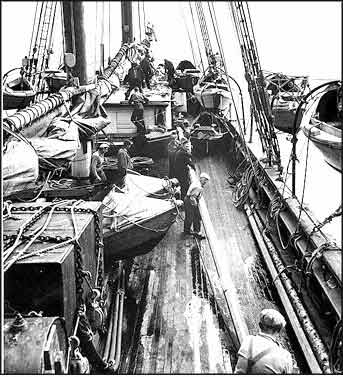

Vision: Convert our working waterfront into an industrial arts district, a place that honors and celebrates the contributions of all maritime workers and a place that people actually want to spend time. Bring arts and culture to where most Kodiak people work (38% of local jobs are in the seafood industry), create opportunities to form new relationships to combat the social segregation in Kodiak, and focus on seafood industry culture rather than seafood industry economics to build greater solidarity on the waterfront and create a more resilient and connected community.

I put together the letter of inquiry, pushed send, and waited. Then, one week before my last day at the Baranov Museum, I received a phone call from New York City. I was one of 80 finalists out of 1400 applicants--- I was invited to submit a full proposal!

Celebration quickly turned to SERIOUS work. Many applicants are organizations, not individuals, and most applicants likely had a real project with a plan in hand, not just a vision. I had two months to convert an idea into a project with partners, a timeline, a budget, an evaluation plan, and more. It wasn't like my vision was small, either. I requested $400,000 to work with local artists to enhance the workplace environment which is Kodiak's working waterfront. And we are talking about the seafood industry, which in Kodiak is highly political and very divisive. In my mind, this project is as much about bridging the divide that clearly exists between the Asian and White communities in Kodiak (which is also an occupational divide between processing workers and fishermen) and enhancing solidarity within the local seafood industry. The waterfront is our greatest asset and the nexus of our greatest challenges.

In the end, I found a statement with which all agree: "Let's use arts and culture to make the waterfront a better place to work." This is a politically neutral statement and all agree it can only help with recruitment and retention of maritime workers.

I felt like a politician for the first month of planning, as I routinely had two to six meetings a day to build partnerships and find supporters. Due to pounding the pavement and articulating a vision that many can get behind, I am collaborating with a cross-sector group of partners who really believe in the project and have offered true support. These include the City of Kodiak, Kodiak Arts Council, Discover Kodiak, Filipino-American Association of Kodiak, Sun'aq Tribe of Kodiak, Kodiak Maritime Museum, Kodiak Community Foundation, Trident Seafoods and APS (North Pacific Seafoods). The thing about these partnerships is that they are real. These aren't "letter of support" partners; many of them have ownership over important parts of the project.

So, what is this project? If funded, we will be doing the following:

Spawn

Local artists will propose temporary or permanent "art interventions" on the waterfront with the intention of making it a better place to work and/or creating new relationships. These interventions can be one-time events (a salsa party in the Sutliff's parking lot, for example) or permanent installations (a snazzy covered bike shelter on Shelikof, for example). All art forms and all artists are encouraged to propose projects, and selected artists will receive money to execute their ideas. Kodiak Arts Council is leading Spawn and we hope to fund around 18 projects in total.

Surface Enhancements

Three large-scale "murals" will be mounted on buildings along Shelikof. The subject matter: maritime trades and people. There will be no bears, eagles, or whales. The art needs to honor our seafood industrial workers and identity. There will be an open call for art for two of the murals. The third will be created through the Sea Lives process (see below). The murals don't have to be 2-D. I think it would be fabulous to use industrial detritus as a medium. Throughout the district I hope that we can use materials that are authentic to the waterfront, like line, nets, buoys, old processing equipment, to create artworks. (The values of the project are authenticity, diversity and inclusion, by the way.) Discover Kodiak is leading this portion of the project.

Sea Lives

This will be a collaboration among a devised theater director (Naphtali Fields), photographer (Breanna Peterson), writer/ producer (me) and a visual artist (TBD). Together we are capturing and co-creating stories from the working waterfront. Naphtali will be leading story circles with processing workers, deck hands, and others whose voices are often not heard. Together they will turn their real stories into a theatrical performance which will be performed during Crab Fest. I will be interviewing maritime workers and producing radio stories from the interviews for KMXT and written stories for online and print publication. Breanna will be taking portraits of all of these participants and others. We will combine quotes from the interviews/ performances with the portraits to create social media posts and large format posters, which will be pasted to buildings along the waterfront. The visual artists will be utilizing this real content from real people to create one of the murals/ surface enhancements in the district. In the end, Sea Lives will highlight the diversity of Kodiak's waterfront and show that regardless of ethnicity, gear type, or profession, all are united through their connection to the working waterfront and their "sea lives"- livelihoods derived from the ocean. This is an internal branding effort, really, one that aims to build greater solidarity in the community.

District Advocacy

Less sexy, but seriously needed. Essentially the leadership team and I will be pestering the City, business owners, and others to integrate art and worker accommodations into their capital and infrastructure plans. I keep returning to bike racks. There is no covered place to lock a bike on Shelikof, even though plenty of folks ride their bikes to work. These small improvements will make the area a better place to work.

So, there you have it. I submitted the proposal yesterday (coincidentally my birthday). In December we will learn if the project is funded. Regardless of the outcome, thanks goes to my friends, collaborators, partners, and the many who were recently strangers but are now colleagues who offered me advice, expertise, and time through this process. What started out as a personal vision in January is now a community-wide dream.

Here's to giving teeth to dreams!

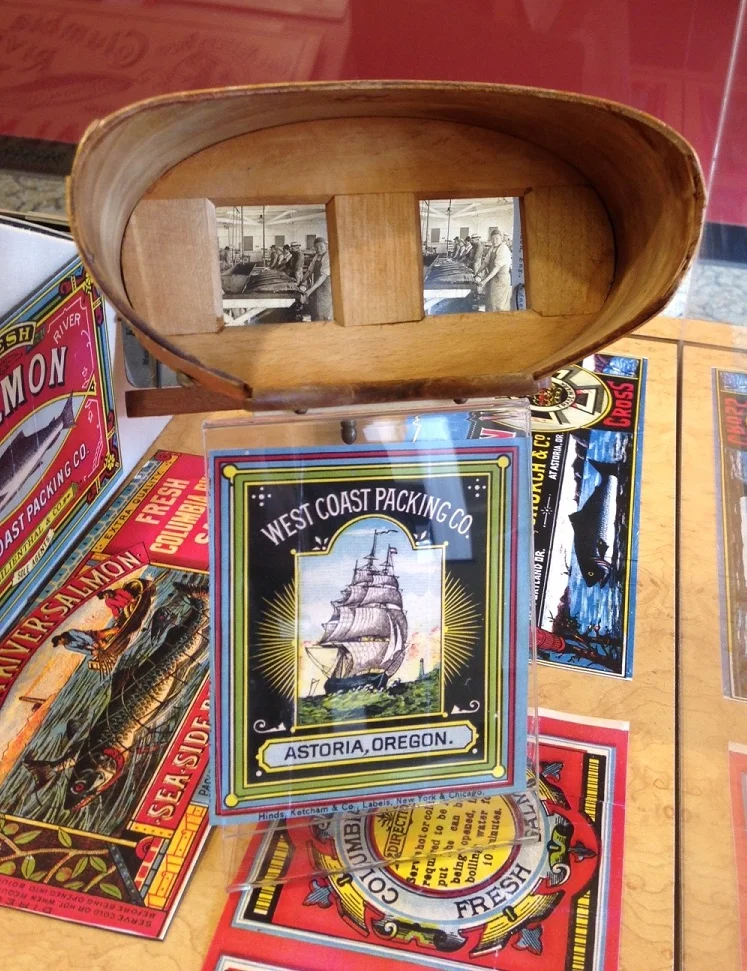

Update: ArtPlace America notified me that I was not awarded the grant. It is very disappointing for Kodiak, as so many people believed in the project and were very excited for its potential. Nonetheless, the conversations and ideas shared and the relationships that were forged through planning for the District have taken root. A business owner on Shelikof St. is adding "gallery" to her store name. The City is financing the creation of interpretive panels highlighting salmon cannery history for downtown. The Kodiak Arts Council started using Fishermen's Hall as a gathering and art space. With diligence, openness, and tenacity, Kodiak will embrace the working waterfront in a new way and see it not just as a place of production, but also as a place of creation.