This article was originally published in the June 2016 issue of Pacific Fishing.

Looking out towards the treacherous mouth of the Columbia River, I noted broken pilings as numerous as porcupine quills along the Astoria shoreline. “Did Mont work in one of the canneries these pilings once supported?” I wondered.

Further inland, letters fading on the front of a nondescript warehouse spell out American Can Company. My imagination produced the glint of flat brights (unlabeled cans) and lids that were once held within. “And to think cans were each hand-soldered in his time…”

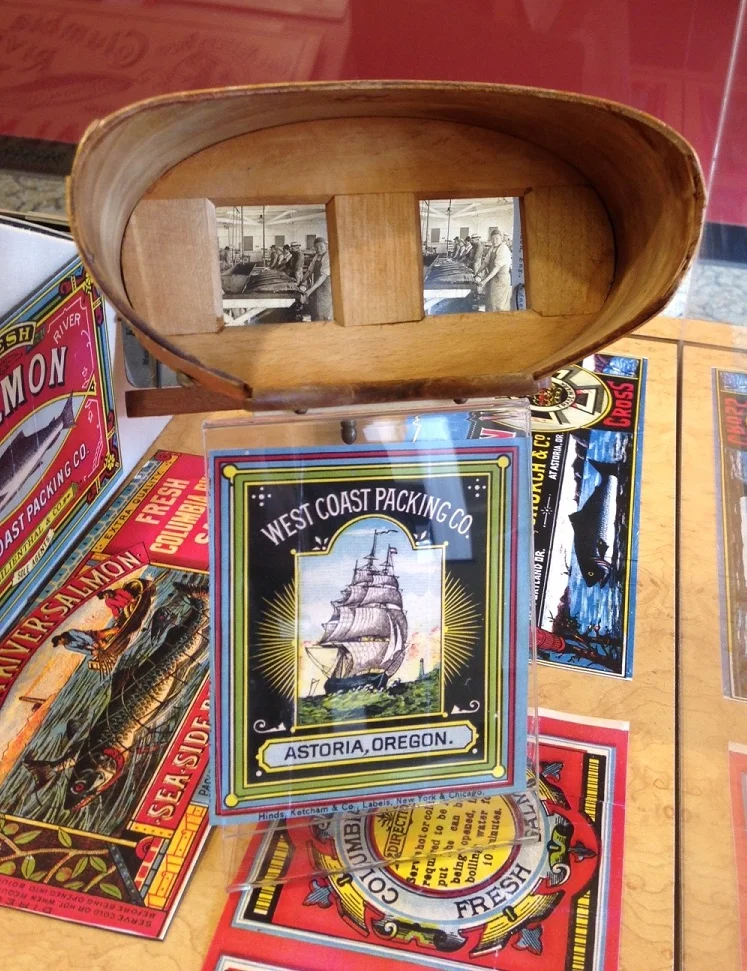

Cannery ephemera and a stereoscopic view of the inside of an Astoria cannery, all on display within a bank in Astoria.

Mont Hawthorne is the affable protagonist within the folksy and informative series of books about the early years of the Pacific coast salmon industry, The Trail Led North and Alaska Silver. Mont arrived in Astoria in 1883 on a sailboat from San Francisco, because “there wasn’t no railroad” to get there. He intended to learn the canning business. I arrived via airplane and rental car, with the intention of learning some fish history and relishing in some fishing literary arts at the FisherPoets Gathering. It ends up that this hardworking cannery man is useful as a long-dead tour guide and as a cannery superintendent.

Mont was but two degrees of separation from the original Hume brothers, who founded the Pacific canned salmon industry. He apprenticed with John A. Devlin, who learned the art of canning directly from the Humes. After five years of making cans, negotiating fish prices, and fashioning cannery equipment under Devlin, Mont became a savvy cannery foreman in his own right who went on to construct and work at canneries along the Columbia River, in Chignik, Kodiak Island, Cook Inlet, and Southeast Alaska. Each winter he returned to Astoria to work with John Fox at the Astoria Iron Works, a business that created prototypes of equipment that revolutionized the packing of salmon over the duration of Mont’s career.

Historic buidings associated with the seafood industry abound in Astoria--- aka Anjuli's nerdy paradise.

It’s an understatement to call the Astoria that Mont sailed into in 1883 a rough town. Vessels engaged in trade and pelagic sealing stopped at Astoria, desperate for new crew. Mont writes that shanghaiing was so rampant that he knew a woman who sold her husband for $100. Walking home at night was always a risk. He remarked,

“ I never went no place without a loaded revolver. No one else did neither. When I’d meet a fellow on that stretch I knowed he could be a shanghaier with a boat tied down below. I’d walk careful-like with my hand on my revolver. And, do you know, every fellow that I met on that stretch done the same thing. We’d pass with our hands on our hips, turned sideways, keeping our eyes on each other, and sometimes backing up as we walked away.”

Mont’s description of the red light district is equally evocative:

“Why, there was one girl show down by the docks where, if you didn’t have the money, you could throw a big fresh salmon into a sort of pen they had beside the ticket-taker and get in that way.”

You can't buy these ladies for a salmon. But maybe for a limit seiner...

Astoria has cleaned up a bit since then, and in the last several years it has started to resemble a mini-Portland. However, stickers in the women’s bathrooms in bars still alert the victims of sex trafficking that they are people, not property, in English, Spanish, and Vietnamese.

Astoria in the 1880s was a stinky place in the summer. Mont recalls that it was typical for him to push five hundred Chinook salmon off the dock at the end of the canning day, each of them at least 40 pounds, due to oversupply. The locals complained; the local wildlife prospered: “With all of them fish on the beach it was hard to keep the bears out of town. It made the womenfolk pretty nervous. They acted like the bears was coming after them instead of the dead salmon.”

Today, the most odiferous offenders in Astoria are fishermen’s most tenured or enemies: sea lions. Forgive me as I take up the parlance of Mont, but to underscore the point: I thought I’d seen sea lions at Cape Ugat, but I ain’t never seen no sea lions like I’ve seen in Astoria. The river boils with them. Boils!

At least a handful of Astoria residents won’t be too offended by how their forefathers dealt with a similar issue. Mont writes,

“One good thing the fisherman’s union did was to hire Clark Lowry to hunt seals and sea lions there at the mouth of the Columbia. They had been making a blamed nuisance of themselves coming in there and eating the fish and tearing up the nets… That man could shoot.”

Mont’s niece, Martha Ferguson McKeown, wrote Mont’s stories. The books are out of print but available at used book stores. I highly recommend picking one up to learn about the heyday of the salmon industry from a man who spoke Chinook Jargon, got an insider view of the Chinese tong wars in San Francisco, prospected during the Klondike Gold Rush, and “got in on most everything up North except the profits.”