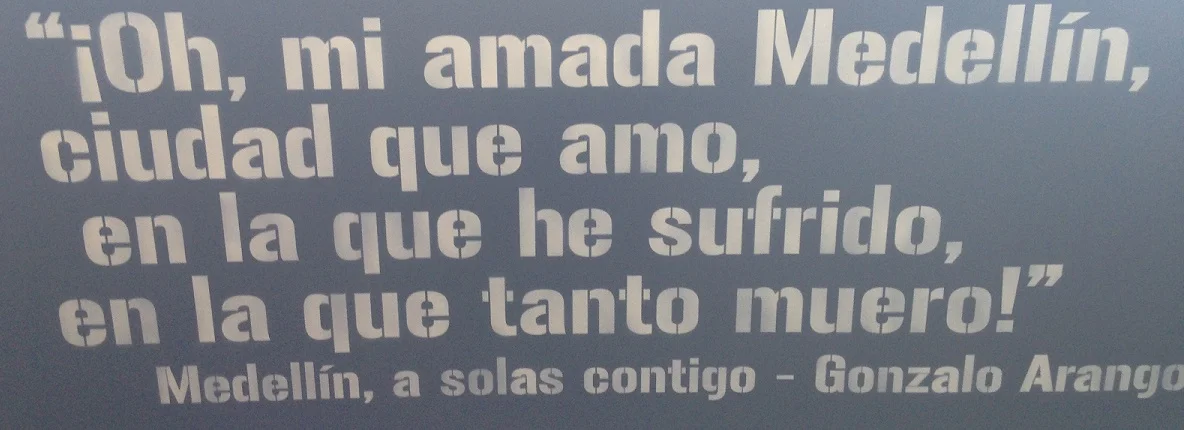

A black wedge of a museum is situated at the far end of a rectangular plaza in a neighborhood called Boston, in the city of Medellin, Colombia. Outside of the Museo de Memoria is written the following, serving as an introduction:

“Seven statements to think of and feel:

We remember

We accept

We ignore

We believe

We resist

We build”

Medellin was considered the most violent city on earth until relatively recently. These statements are for intellectual grappling, for emotional resilience, as Medellin residents heal, survive, and thrive following the decades of chaos.

I turn to these statements now as I conjure words to articulate the shift that occurred during the short ten days I was in Medellin. My world changed while I was there. My previously quieted stories found paper. And I am emboldened to share a terrifying experience that I would not have shared before now. I look at those statements and wrap myself in the resiliency of Medellin. I am fortified.

We remember

“A grenade exploded right here, but nobody remembers,” said tour guide Pablo, pointing at a mural outside of a metro station in downtown Medellin. The mural depicted gold mines, railroad tracks, coffee plantations and the chronological development of the city. But missing from the mural is the industry for which Medellin is most associated in the minds of the world. Missing is the identity which Paisas--- those from Medellin--- are desperately trying to molt, the enterprise which pulled the pin in the grenade that nobody now recalls. Cocaine.

Pablo tells the group of tourists that no one remembers a single grenade when there are entire decades of atrocities to forget.

I was in Medellin to dance salsa, to get a sense of a region in Colombia that I had never visited, and because of a last minute, cheap mileage ticket. But unexpectedly, as Pablo uttered those words, the free tour that was to serve merely as my introduction to the city reminded me of something I don’t often recall.

As Pablo went on to describe the kidnappings, the explosions, the paramilitary and guerilla wars, I remembered that it was because of Colombian cocaine that I am Alaskan. It is because of Colombian cocaine that I was likely born.

We Accept

My dad was a drug dealer. Sure, he sometimes was a fisherman, and once he had an Afghan “rug” importing businesses, but all of these were side schemes that helped him either access drugs or launder money from drug sales. Heroin was his drug of choice, but it was cocaine that brought him to Kodiak, Alaska, around 1980. Then, when cocaine was king in Medellin, it was king crab that ruled the island of Kodiak, Alaska. And Joe Grantham, king of nothing but get-rich-quick schemes, saw an opening.

Shutup Joe Grantham, king of get-rich-quick schemes.

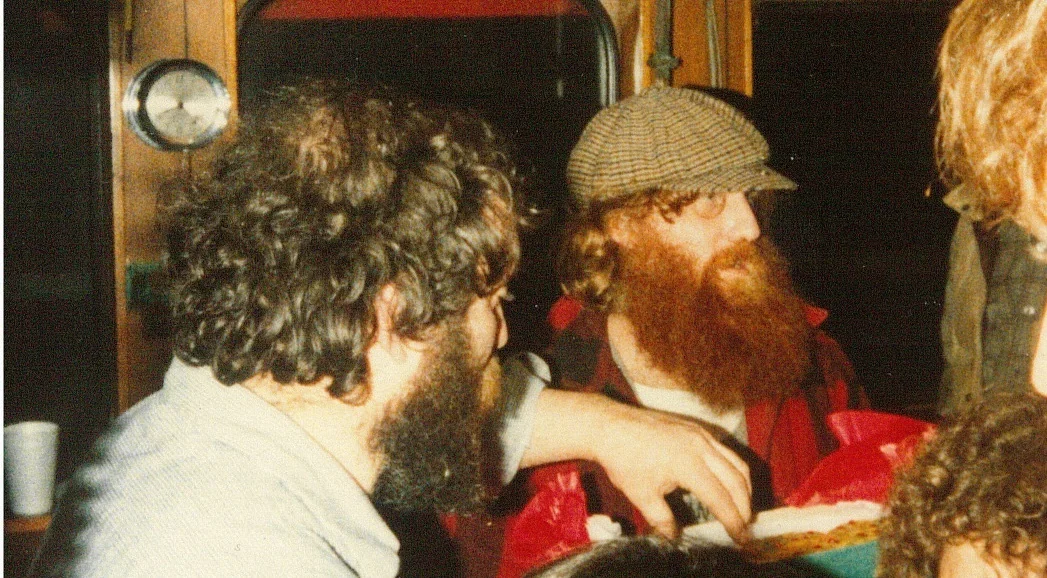

Kodiak and Medellin had little in common in the 1970s and early 80s aside from one key linkage: money. Kodiak in 1980 was a small town on a big island full of taxidermy king crabs hanging from the walls of smoky bars. Gold nuggets on thick watchbands, clasped with gold king crabs adorned the flannel-clad wrists of young, bearded men. Plenty of those men couldn’t properly fold their wallets because of the quick wealth of king crab fishing shoved inside. Rusty trucks, crab pots stacked high on the back decks of boats, unpaved roads, go-go girls and strippers: this was the reprieve that Kodiak offered from rabid winter fishing in the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea. From 1979-1980, boats delivered over 14 million pounds of king crab to Kodiak’s docks. The town was rough, flush and wild from it all.

But the day that my parents’ best friend stepped off the barge on which he lived to dial my dad in Portland, there was something missing from Kodiak. There were young men, there was cash, but there was no blow, he reported. And he knew that my dad had just what Kodiak needed.

My dad had been dealing for over a decade by then. He started by selling in Eugene, Oregon and graduated to dispensing LSD and hash from a VW van in Europe in the late 1960s. After returning to the US, he established his Afghan “rug” import business with several associates, including his best friend from childhood named Jimmy Smack, a Cuban with a good connection, and a Vietnam vet who knocked around his slender, brunette wife. Her name was Pam, and she and my father fell in love.

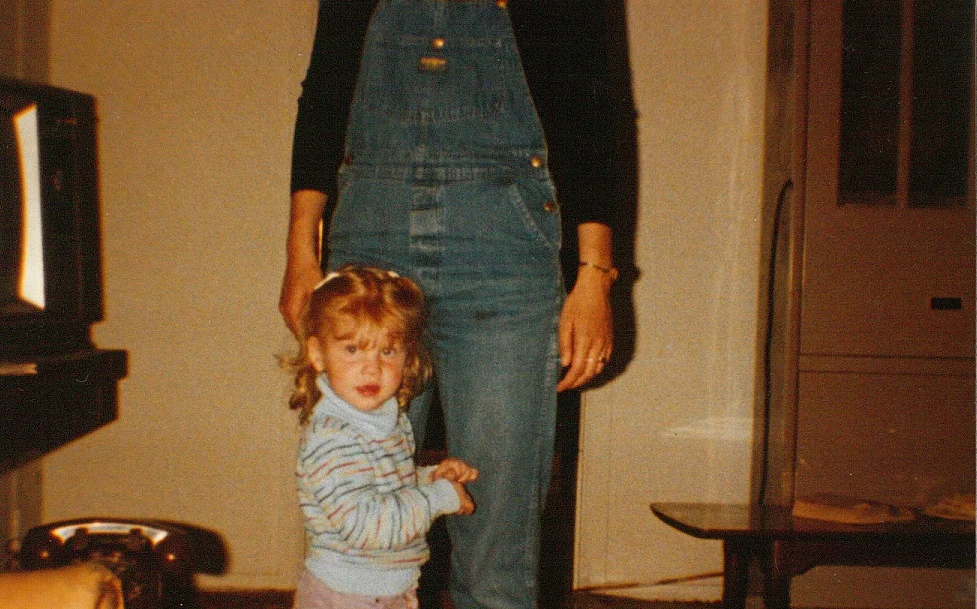

My parents packed their bags and arrived in Kodiak. My dad carried tens of thousands of dollars in cocaine. Mom started cocktail waitressing and Dad bought a boat with his earnings. Two years later, the king crab fishery crashed, never again to recover. That same year I was born, and two years later my brother Gustav was born. My parents separated following Gustav’s birth. “Your dad chose drinking over our family,” my mom told me one day.

Even as a child I knew that my dad was a drug dealer; no one needed to tell me. For my seventh birthday he gave me a gold, diamond and amethyst ring. I never valued it, since I knew it belonged to somebody else. I knew what cocaine was, though I don’t remember seeing it and could only articulate that it was snorted and made people talkative. I preferred to spend time with my dad when he was doing drugs rather than drinking. When he was drinking, he was homeless and lived in the plaza in downtown Kodiak. Mom would barely let me and Gus see him. Sometimes he would get sober long enough so that Mom let us spend the day with him. Dumpster diving constituted our visitation.

But when my dad was high, he was quicker, more present. He told enthralling stories and was completely delusional about his exploits, living up to his nickname of Shutup Joe. I was scared of the potential of this manic energy. It was during this time that I saw a handgun tucked in the back waistband of his pants when he stood up to leave. It was around then that he came to our door, blood pouring from his head. Mom made him sit in the mini-van as she tended to his wounds. She wouldn’t let us kids see him. She kept returning to the house to empty an aluminum salad bowl of bloody water and red-stained washcloths.

We Ignore

When I was twelve years old, my dad was arrested for selling cocaine and heroin. I sobbed onto my mom’s sleeve the evening when she told me. I wasn’t sad that he was arrested; I was mortified to be publically outed as the daughter of a drug dealer.

“In Medellin, we live with the stigma of the drug war and we are doing all that we can to move past it,” Pablo tells the group at the end of the tour. We were standing in Parque San Antonio, near an obliterated bronze sculpture of a bird. In 1995, a still-unknown group hid a bomb in a Francisco Botero statue and detonated it during a public concert. Twenty nine people were killed.

Parque San Antonio, Medellin

Medellin is a different place now, an epicenter of innovation, art, and culture within Colombia. I walk the streets of the posh El Poblado neighborhood at night without concern for my safety. And many Paisas want more than anything for their city’s reputation as the most violent on the planet to be forgotten.

I understood this in my gut. It’s through forgetting- or better, avoiding active remembering- that I’ve maintained my cheery disposition and optimism that borders on naivety, regardless of the losses I sustained in my young life. Survival sometimes relies on a short memory.

We Resist

Three nights before I was to leave Medellin, I opened my eyes to the night-filled room and a saw a hunched figure at the foot of my bed. At first I thought it was a remnant of my dream, persisting as my brain yawned awake. Was it a child, folded over in the shadows? Yet the figure’s mass solidified rather than dispersed as I became conscious. Then the being shifted. It became clear, sat up straight. It was not the visual aftertaste of a nightmare, it was not a child.

It was a man.

A hoarse holler came from my solar plexus as the man shuffled his hands near his groin, rose up from the ground, and slunk out of my bedroom like a shadow in the rising sun. He uttered but one word, “Pardon.”

A cocker spaniel puppy came into my bedroom the moment that the man left. He whimpered and trotted out as I scrambled to lock the door behind them both. The puppy really lived in that house. It was not a dream. That man really broke into my room in the middle of the night. That really was Manuel, the son of my host, masturbating at the foot of my bed.

I stared in terror at the locked door for the rest of the night. I can’t remember ever being so frightened.

When I summoned the courage to open my bedroom door the next day, Johana, mother of Manuel, was waiting for me. She was crying, ashamed, horrified at what had happened. She told me that Manuel had a foot fetish and had done this before, to other women. That he was seeking psychological help, that she pleaded with him to practice strict self-control. She told me she had been raped when she was young, and she knew the fear that I must be feeling.

Manuel never touched me, but he violated me. He objectified me. He gave me a glimpse of the kind of terror that too many women feel too often.

I left the apartment and took an elevator to the ground floor. The sight of the quiet doorman brought my heart into my throat. I crossed the street and the man carrying a box of gum and candy bars made my hands tremble. For the first time in my life, every man that I saw seemed a potent threat to my safety and the autonomy of my body, of my being.

The view from my bedroom.

By the time I had walked the 10 or so blocks to the Poblado Metro Station, I was no longer uneasy in the presence of men, but something remained. Like a whiff of a pheromone, or a heart-flutter, or a subtle shift in temperature--- a quiet yet perceptible difference from the conditions before.

I thought of my previous experiences with sexual and physical violence. I remembered the domestic abuse I witnessed as a child. I recall fleeing our home late one night after my dad choked my mom, her profile slipping from light into shadow as we drove to where we would be safe.

I thought of the summer that I turned sixteen. I was working as a salmon fisherman at a remote setnet site. A crazy crewmember who was in his 50s told all he could at the end of the season that my mom had pimped me out to him, that we spent the season having sex. Other men threatened to kill him to avenge my honor, but no one went to the police. No one offered me help. It was a delusion, but one that many believed. They believed it so strongly that a man I grew up calling uncle looked at me across the Christmas dinner table and called me a “little whore.” My voice was ignored. My shame was deep even though I did nothing at all.

I thought of the times that men persisted and persisted even though I said no and no and no.

The very next night, I watched as Donald Trump was named president. I sobbed into my pillow. I felt a second dose of the fear from the evening before. A man who brags about accosting women will be president. A man who had demonstrated he does not believe in consent will lead the nation. A man who, through his words and actions, condones sexual predation like what I had just experienced soon will have the largest pulpit in the world.

We Build

I needed to clear my head. It was my last day in Medellin. I needed a walk. I stopped in Plaza Lleras and tried to be present to my environment, to soak up the happy bits of Colombia that ensorcelled me during my first trip to the country two years before. I stood still in the plaza, watching a man paint lips onto a saxophone player on his canvass, when two women in shin-length skirts approached me.

“Are you alright? Are you lost?” The taller asked, noting my distraught face.

I told her I was not lost, just scared for my country and for the world. She handed me a Watchtower and assured me that the prophecies were coming true. The end times were near. The Kingdom of God was just around the bend, and when that moment came, God will replace corrupt politicians.

“I want to work for the good of the planet and humanity now, not wait for some imagined future,” I told them, walking away with a shaking chin.

And then I recalled Pablo, my tour guide of the week before, telling us travelers about the election of 1990 in Colombia. Three of the four presidential candidates were assassinated.

The fear that hovered in my solar plexus was real, but it was relative. If Paisas can walk the streets of their city, trod on sidewalks once splattered with blood and gather on street corners that were the sites of massacres just a decade ago, I could handle my fear. I too can turn it into strength.

A short film in the Museo de Memoria depicted resilience. A spot of ink was dropped on a tab of paper and submerged in water. “My life is attacked, but I can transform wounds into love, hope, courage,” read the narration as the ink blot spread upwards, turning into a slender flame, “and turn tragedy into a vital force.”

I can convert the terror I felt from two nights before and my outrage about the election into righteous anger. The fire of that anger will turn into embers of empathy and resilience.

Those words- empathy and resilience- are not quiet words. They are not passive words. They are bold, they are wise. They are feminine. I understand that by sharing my story, I can hold space for those who do not speak. Perhaps I can give strength to those who do not speak. It was when Pablo shared the story of the drug war in Medellin that I received the courage to share my story, as the daughter of a drug dealer and addict, as the recent victim of sexual aggression, and a lifelong victim of misogyny and rape culture.

In Medellin, I realized that the city’s violent past is my past. The city’s drug problems were my family’s drug problems. When Medellin was the most violent place in the world, it also ruled the worlds of hundreds of thousands of families affected by coke, crack, and the fruitless war on drugs. We are all Medellin.

Likewise, the fear that I experienced the other night as a man made me a part of his sexual fantasy without my consent, the shame that I felt when those who claimed to love me treated me like a harlot as a sixteen year old, these are experiences that women (and some men) around the world share. We are united as victims of patriarchy.

But the potential of our resiliency is boundless. It will transform our world.