Lines, hooks, and pots. Using these tools, humans have wrested food from the water for countless generations. Yet innovations in fishing techniques and fishing tools pervade the industry, especially in the rare moments when new fisheries are executed. Take the new Gulf of Alaska black cod pot fishery, which inaugurated just this year. Fishermen across Alaska are sharing secrets and exchanging hints as they learn to tempt black cod into pots and longline with something other than hooks as they embark on a new era in their fishery.

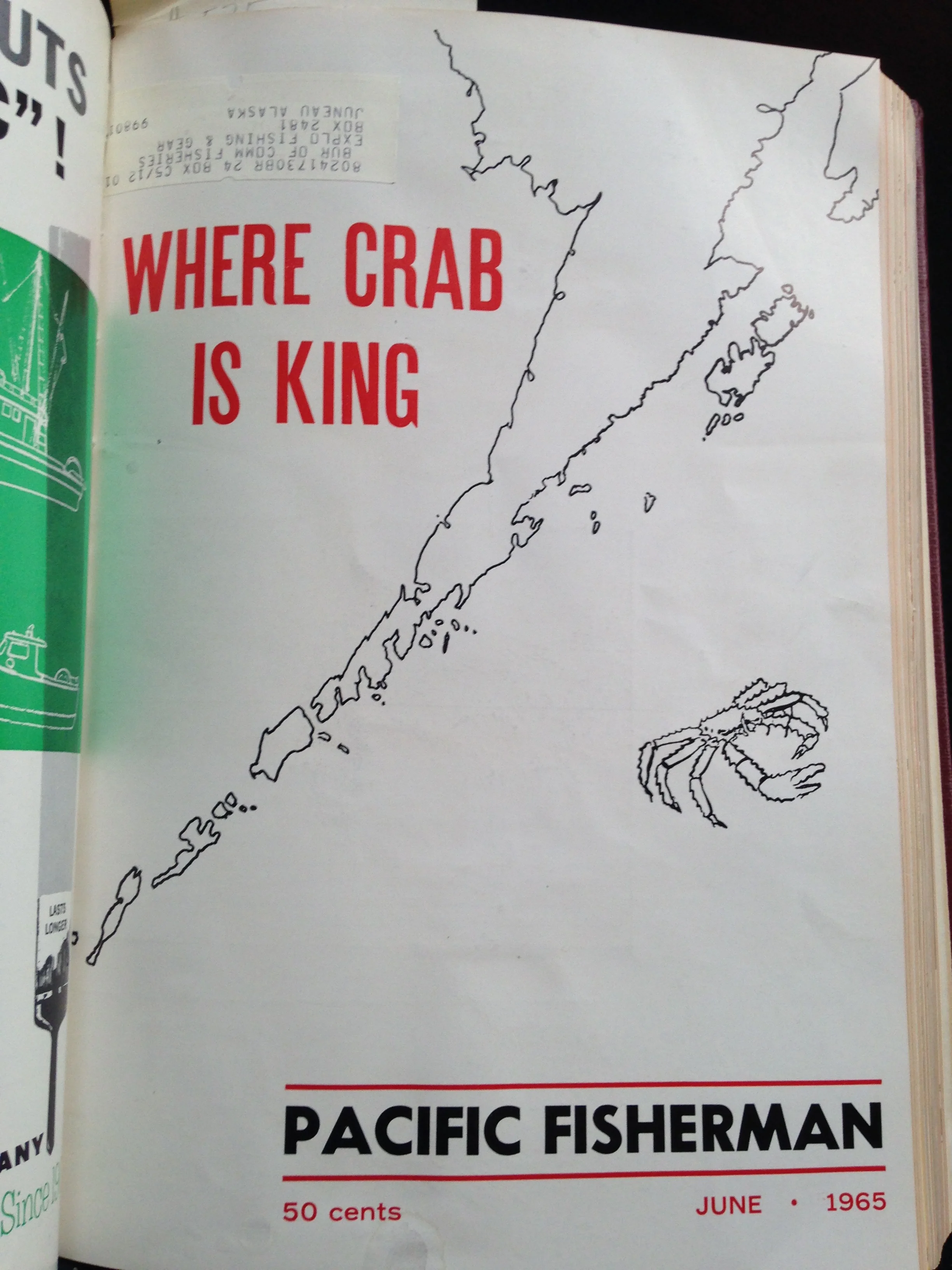

Just as these black cod pot fishermen are making it up as they go along, the king crab fishery was another venture that was invented as it was executed. The first commercial king crab fishing happened in Seldovia in 1920. It took several more decades for the fishery to gain any traction, but when it did, it happened quickly. Kodiak emerged as the epicenter of the king crab fishery. In 1950, fishermen delivered 64,882 pounds of king crab to Kodiak, but in 1966, that number had grown to 90,750,000.

The Kodiak Maritime Museum’s oral history project, “When Crab Was King,” records the development of the king crab industry as the fishermen recall it, including innovations in gear and techniques. Interview subjects note that early king crab pots were patterned after dungeness pots. They were round and about six feet in diameter. These early wooden pots were made of netting manufactured for salmon seines and fish trap wire. They would last for just a season. Early crabbers also used tangle nets and trawl gear to wrangle king crab from the bottom of the ocean. Tangle nets were prohibited after 1955, and trawls were outlawed for crab fishing in 1961.

In one oral history, Nick Szabo relates, “A lot of this stuff got started up in Seldovia, because a lot of the guys that pioneered the king crab fishery that later moved [to Kodiak] came from Seldovia.” A new kind of tunnel for king crab pots is one such invention credited to Seldovia fishermen. Early pots had a vertical tunnel and a trigger, but fishermen noted that the king crab would back out of the pots once they hit the trigger. Szabo reports that Seldovia fishermen invented the angular tunnel, from which the crab could not escape as easily.

By the 1960s, rectangular steel pots had replaced the round pots, because fishermen figured the shape maximized the use of deck space, as compared to stacked round pots. This in turn increased the fishing capacity of the boat. Smaller boats had six foot by six foot pots, while larger boats had seven foot by seven foot, and the largest vessels produced eight foot by eight foot pots. Szabo recounts that, “…When the crab fishery started declining, then it started to back off to the six by [six] and seven by [seven] because they were easier to handle. The eight by [eight pots] were awful heavy and they were sort of cumbersome to handle on deck… Someone would try something different and then, you know, other people would copy it if it was successful.”

Wayne Baker recalls the different styles of crab fishing. “When we first got up here there was an Oregon way to fish, and there was a Ballard way to fish and how to do things. The Oregon guys would bundle their lines outside their pots and do it like they were longlining, like they did dungie pots... A lot of extra work, but we didn't know it at the time.” When Baker headed out west, he learned the Ballard style, for which, “everybody boxed up all the line because there are shorter shots, because it is shallower out in the Bering Sea. And you just throw everything in the pots. It's cleaner. That's the way that everyone does things now, we all got a little bit smarter.”

There were no sorting tables, and when it came time to empty the pots, they “just dumped all the crab down on the deck and chase[d] them around like chickens. We would get done and there would be crab scattered around the whole length of the deck,” Baker recalls. Later, he saw a photo of his brother crabbing. “They were using the shrimp totes. They would dump their crab into these shrimp totes. And it was like a revelation. It was like, holy cow that is the greatest idea that we ever saw!” His skipper hollered at Baker the first time Baker dumped crab into a tote, but saw that this simple innovation saved time and energy. “Back then we ran six, eight [pots an hour]. If you ran ten, twelve pots an hour you were going good… Now we run eighteen, twenty pots an hour pretty steady,” Baker notes.

The ragtag fleet was composed of old military scows, pocket seiners, and more. Vessels purpose-built for crab fishing didn’t leave the shipyard until the 1960s, and even then, didn’t predominate within the fleet until later. The boats were not designed to accommodate tanks full of water and crab with thousands of pounds of pots stacked on the back deck. This meant that disaster struck quickly and frequently. Marcy Jones, namesake and former co-owner of the Marcy J, recalls that there was no requirement for boats to carry life rafts, and survival suits were yet to be invented. She had seen crab biologist Guy Powell sporting a wetsuit, and bought one for her husband, Harold, to bring out fishing with him, “And he was the first person, so far as I know, in the whole fishing industry that had any kind of a suit to put on to stay warm in case something happened.”

While crab fishermen made up the fishery as they went along, marine architects worked to design boats designed for the fishery, the Coast Guard, insurance companies, and boat owners collaborated to improve safety, and seafood processors came up with new ways to preserve and market the catch. The king crab fishery, like the new black cod pot fishery, proves yet again that necessity is the mother of invention.